In the United States, both the Nexus S and the Galaxy Nexus were sold in 4G versions for the networks that supported the technology, but with the announcement of the Nexus 4 today, many people were left wondering why Google seem to have back-pedaled and failed to offer a 4G version of their new flagship. After all, even the latest iPhone has LTE.

When the Nexus One was released, Google intended to sell it only via its web store. Carriers, particularly those in America, exercise a lot of control over the phones on their network, filling them with bloatware and never releasing updates. The Nexus was intended to circumvent the carrier’s demands and provide users with the pure Android experience. Unfortunately, the Nexus One (and subsequent Nexus phones) did not sell well, and Google was forced to make deals with the carriers in order to get its phones into the hands of Android enthusiasts. In Australia, the Nexus line was distributed through Vodafone originally, and the Galaxy Nexus was available on Telstra and Optus as well.

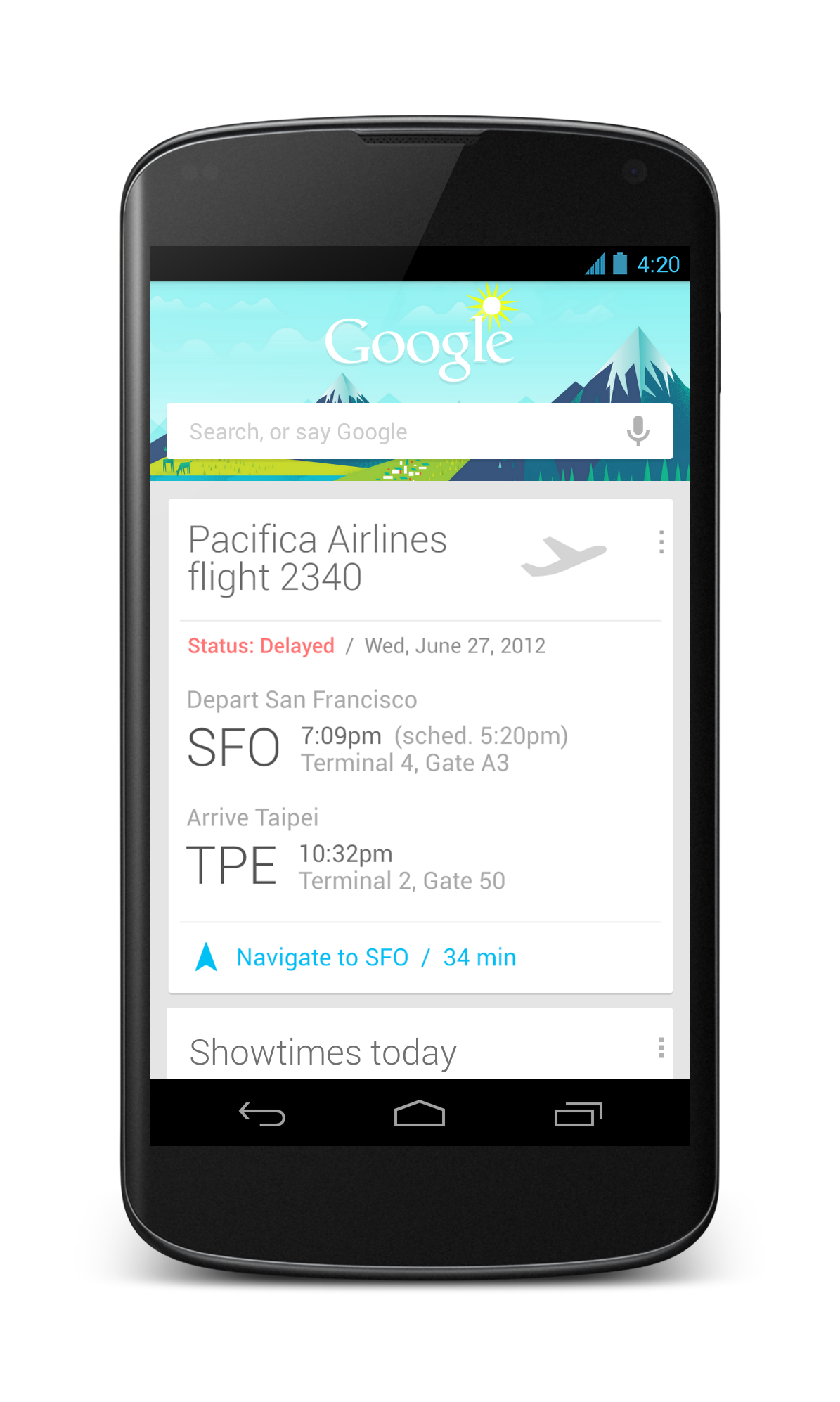

Unlike the two most recent Nexus phones, and for the first time in Australia, Google are selling the Nexus 4 directly to consumers through the Play Store, unlocked for a paltry $399 (to compare, the cheapest iPhone costs $799 outright). The Nexus 7 was also ridiculously underpriced, a factor which contributed to its enormous success. Google wants to get Nexus devices into as many hands as possible and so it wants to make them as appealing as possible. For Google to reach the low price point that they did, they had to make some concessions, and considering that the Nexus 4 is about as high-specced as a phone can get, LTE had to go.

LTE is still a new technology. In Australia, only Telstra and Optus have LTE networks (although Vodafone plans to introduce an LTE network early next year), and even in Melbourne, Telstra’s 4G network only extends 10 km from the city centre. Internationally, most of the larger carriers are at similar stages of development with their own LTE networks, but owing to a number of factors, there are significant interoperability issues between the different networks, requiring OEMs to create different versions of their handset for different markets. This is an expensive exercise, and unless there is a huge potential market to be exploited, or someone else funds it, the development of multiple (almost) identical devices just isn’t going to happen.

Compare this with 3G (UMTS/HSPA), a well-established technology with a high degree of interoperability (outside of the United States, anyway), which is almost universal in its compatibility. You can buy an unlocked 3G handset in Australia and use it almost anywhere in the world with any SIM card you like. It’s awesome. By sticking to 3G, Google can create one device for the entire world, thus minimising its R&D costs, and passing the savings onto you. Andy Rubin, said it himself: ‘Tactically, we want to make sure the devices are available for every network on the planet’. Without carrier involvement, this just wasn’t going to happen with LTE, and Google can’t guarantee the pure Nexus experience if the carriers put their hands in the pie.

Basically, it comes down to cost.