It’s little wonder that people are growing more and more concerned with how their activity online might be stored and monitored, with Australia’s recent passage of mandatory data retention legislation (and the virtually unfettered access to that information by law enforcement agencies). It seems that we’ve learned nothing from the somewhat disturbing access that the USA’s National Security Agency has to the private lives of American citizens through the information that came to light from Edward Snowden.

I don’t think it’s just people with something to hide that are looking for ways to maintain a bit of privacy for themselves; all manner of people might hold legitimate concerns for the privacy of their online activities, and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with trying to take steps to keep what you do to yourself (as much as possible).

Australia seems to have been jumping on board, too. VPN usage in Australia has shot up in the last six months according to PureVPN, a provider of global VPN services. It all started around October last year, which was the same time that iiNet started battle with Dallas Buyers Club which would (eventually) require the turning over of subscriber data to DBC for the purposes of pursuing copyright infringement claims. A lot has happened since, including the passage of mandatory data retention legislation, as well as proposals to block access to overseas piracy websites, and a new industry code that brings in a ‘three strikes’ policy for online copyright infringement.

It isn’t just people who infringe copyright who might want protection though; do you browse lawful content but not want to get caught up in our data retention scheme? Do you conduct sensitive business that you don’t want some curious law enforcement official browsing across? Jokes aside, there will be a good number of people who have nothing illegal to hide who need a way to protect what they’re doing from prying eyes, and if Google search results are any indicator, VPNs are on the up and up.

Of course, it isn’t just protecting our online footprints that drives VPN use, with Australia often left waiting for access to content that’s widely available overseas. Now that Netflix is in Australia, that demand has likely waned a little, but until very recently, use of a VPN to circumvent geographical content restrictions has been significant.

Let’s take a look at concerns about metadata, though, because its something that not everyone understands.

What is metadata?

There’s a few useful analogies to define metadata, and these two are probably the most well known:

- If you make a phone call to someone, what you say to the other person is content. The number you rang from, the number you rang, the date and time of your call, your account number, personal details, and potentially the personal data of the person you rang are the metadata that could be stored.

- When you send someone a letter, the content of your letter is the content, and the metadata is your recipient’s address, your return address if you wrote one, the date you posted the letter (or when it was postmarked), and perhaps where (or the region) where you posted it.

In the digital age, the line blurs a little. When you access Ausdroid, for example, there’s an absolute swathe of metadata up for the taking, including:

- Your IP address

- Details identifying your computer, software, browser, and more

- The date and time of your access, and potentially where you accessed from

- What URL you visited

With a comprehensive metadata retention regime, accessing the actual content of a communication becomes largely unnecessary. Consider this scenario, of which various permutations have been used to demonstrate the risk this poses many times over:

At 7pm your phone records show that you rang someone else’s mobile, then a restaurant, then that person’s mobile again. Later that evening, your email records show you received an email from [email protected]. The next morning, you rang three nearby chemists, and two days later, you rang the person from a few nights ago 15 times for a duration of no longer than 30 seconds each, before ringing a sexual health clinic.

You don’t need to know the content of those emails or phone conversations to figure out what might have happened, based purely on the metadata that is captured and retained. There’s a number of plausible explanations, but you don’t need to be too creative to come up with a few guesses. Do you want that kind of information available to law enforcement without a warrant? Probably not.

What’s the big deal?

Metadata retention doesn’t just touch on your emails and your phone calls. Your smartphone captures an awful lot of data about you, and transmits a lot of it too, and that information could potentially be stored as well. What you do on social media, the movies you download, and the people you contact in the pursuit of your recreation and your job could all be swept up, and if you don’t want your activities recorded, too bad. Right?

Not exactly.

How does a VPN address all this?

Let’s be honest, most people in Australia who know what a VPN is will probably associate it with a way of accessing Netflix, and many others are probably business users who know that they need to use a VPN to access things, but might not know exactly how it works.

In its simplest form, a VPN is a secure, generally encrypted tunnel between you and some other point. In the business sense, it allows you to access a corporate network as if you were at work, securely and remotely. For everyone else, it’s a way of sending your internet traffic over an encrypted tunnel to some other place, where it can then transit the internet and access the content you want.

When you use the internet without a VPN, your data can be tracked, as we’ve discussed above. When you use a VPN, there’s very little to see. Your ISP (or mobile provider) can detect that your device or computer is online, and (if they’re looking closely) that you’re sending a lot of traffic to and from a likely VPN endpoint. However, they can’t see what that traffic contains, and so your online browsing habits, email messages, and everything else are almost completely hidden.

Of course, this covers just the transport of your data, and if your data is otherwise stored in Australia, it might be accessible anyway — for example, using a VPN to access your Australian email account probably isn’t going to be of much use, though it does make it a little more difficult to demonstrate that it was you who was accessing it.

Better yet, you can use a VPN on your home computer, your mobile phone, or even your router, protecting all of your home devices at once.

PureVPN and its benefits

There’s a number of providers out there, and the list is steadily growing — VPNs are big business, and likely to continue to be. PureVPN are one provider, and we won’t hide facts — they approached Ausdroid with a story idea on VPNs and a pointer to their service. Other publications in Australia have done similar things, but we’re pro security and being careful out there, so we thought it wouldn’t hurt to share their messaging with you.

PureVPN offers its users access to 80,000+ IPs from 450+ servers in 100+ countries to hide their real identity and become completely anonymous on the internet. Plus, PureVPN provides 256-bit of military-grade encryption and a vast variety of protocols to encrypt data and secretly send it over the internet.

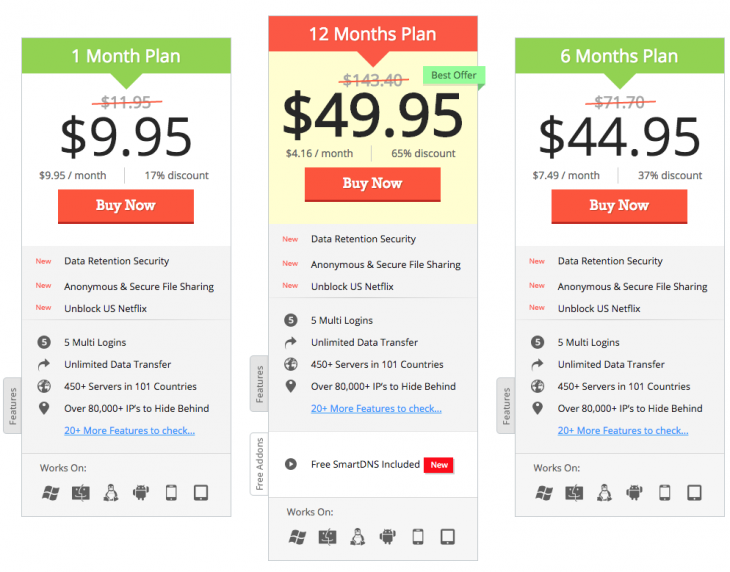

They offer a range of affordable plans that you can use across all your devices, and for those who are less technically savvy, there’s an app for Windows, Mac, iOS and Android to help make setting up a VPN as simple as can be. Pricing starts at $US9.95 on a pay by the month plan, and drops to as low as $US4.16 per month if you pay for the year in advance, as per below:

In addition to the pricing set out above, there are additional services which you can add if you need them. SmartDNS deserves particular mention, as it allows connected devices (such as TVs) to access US content without needing to use a VPN. It’s $2.99 a month, or included for free on the annual plan. Other options which pro users might what include a dedicated IP address, streaming-optimised services and additional security options.

A key feature, depending on your needs, is that you can change which server you use as you see fit — if you’re accessing Australian content and just want some privacy, use their Australian server for fastest response times. If you’re wanting to hide your activities a bit further, use an overseas server. To access US-only content, one of their many servers based across the US is probably a good idea.

You can access any of these, and change between them at will for the monthly plan cost. Better yet, you can have five devices connected at once, so you could have your computer at home covered, and your mobile while you’re out and about, and a few other things as well.

PureVPN works using PPTP, L2TP, and OpenVPN support. OpenVPN is considered slightly more secure and faster than L2TP, it isn’t always as easily configured and isn’t natively supported on all platforms. L2TP is widely available, very secure and reasonably fast making it probably the best of both worlds. Depending on your needs and your focus, PureVPN has a VPN platform for you.

If you want to sign up for a PureVPN account, you can do so today and take advantage of a 10% off sale as well.

This article on metadata, data retention and online security is a paid editorial from PureVPN. We’ve tried their service and we stand behind what we say here.